Two New Books Add Flare to Your Campfire

The recipe for Skillet Squirrel with Dried Morels may sound like a meal scrounged up in an episode of the Discovery Channel’s Survivorman, and the variation beneath it suggesting that cooks use "young muskrat" if no squirrels are available might even be reminiscent of a Fear Factor challenge, but it’s only one option the long menu that A.D. Livingston’s latest cookbook offers for your evenings by the campfire.

Skillet Cooking for Camp and Kitchen (The Lyons Press, $14.95) isn’t exclusively for the hunter at the deer camp, though. After all, the book is subtitled More than 101 Modern and Old-Time Recipes for Jackleg Cooks and Practical Housewives and includes instructions for preparing even the most traditional fireside fare.

Take, for instance, Trout Hemingway, a recipe Ernest himself wrote up in his own outdoors column in the Toronto Star. As sparse as the Hemingway style itself, the recipe simply consists of trout, bacon, cornmeal and Crisco.

What this recipe represents even more accurately is Livingston’s message that skilletmanship is an art in which the how is more important than the what: "It’s a hands-on kind of cooking, in which success often depends more on technique, skill, and tender-loving care than on a complicated recipe with a long list of ingredients."

Livingston encourages camp cooks to find the right skillet for the right recipe and doesn’t rule out flea markets and junk shops as the places to do so.

But simplicity doesn’t mean that this cooking columnist for Gray’s Sporting Journal ever skimps on the more unique dishes. In an entire chapter dedicated to "Exotic Meats," Livingston opens readers’ minds (and maybe even their mouths) to such treats as cod tongues and fried soft shell turtle.

And while Livingston suggests buying your ingredients for A.D.’s Cricket Crisps at the local bait shop, his next chapter, as with the Hemingway dish, again disarms the reader with a variety of fruit and vegetable favorites like onion rings and fried apple slices.

A common element to many of Livingston’s not-so-common recipes, though, is the mushroom, an ingredient that need not bring you to the bait shop or even to the grocery shop. By foraging the very woods in which you camp, you can gather the main ingredients for several of Livingston’s dishes, and while mushroom hunting can be intimidating- and even dangerous-, there’s another new book that can help you along the way.

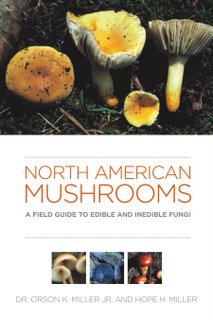

North American Mushrooms: A Field Guide to Edible and Inedible Fungi (Falcon Guides, $25.95) is a 592-page encyclopedia that is essential for the risky business of mushroom gathering. Virginia Tech professor Dr. Orson K. Miller and his wife, mushroom expert and cookbook author Hope Miller, together create a comprehensive guide that teaches readers everything from a mushroom’s anatomy to its geographic distribution.

The challenges of the forager in search of edible mushrooms on our continent is evident in the size of this guide, but the Millers’ expertise make this task a safer one. The authors, however, use designations as varied as "edible" to "poisonous" to "edibility unknown," so they stress the rule of "when in doubt, throw it out!"

The Millers, however, do an exceptional job of diminishing that doubt. From the start, they insist that a spore print be taken for positive identification and explain just how to do that. In addition, the Millers’ text is complimented by 600 color photos that make this guide a must-pack for the mushroom hunter.

Among the recipes in Skillet Cooking that call for mushrooms are Alaskan Dried Mushroom Camp Gravy, Easy Wild Mushroom Omelet, Mushroom Smothered Chicken, Sauteed Chanterelles, Wild Mushroom Fritters, and, of course, Skillet Squirrel with Dried Morels.

By combing the know-how in each of these books, you can practice the self-reliance we all look for in the woods. Just as the campfire is a source of pride for its builder, the meal cooked upon it should be, too. Both titles are practical guides that can each add to the skills of the most experienced outdoorsman. By packing them with the skillet itself, whether you prefer squirrel or a muskrat, you can rest assured that the morels in that skillet will only add more flare to the fire.